The journey back

(1) Since 2005 I have travelled regularly from my home in the north of Germany to visit my daughter in Genoa, the historical port on the north west coast of Italy where she lives. These routine visits take place three or four times a year, for a period of four or five days each time.

(1) Since 2005 I have travelled regularly from my home in the north of Germany to visit my daughter in Genoa, the historical port on the north west coast of Italy where she lives. These routine visits take place three or four times a year, for a period of four or five days each time.

(2) In conversation I often remark on the convenience of my German home, given its location roughly half way between my parents in the south of England and my daughter in Italy. Nevertheless, my regular to-ing and fro-ing on family visits is a symptomatic part of a divided sense of “home” and belonging, pulled in conflicting directions between Germany where I have lived and worked for the past 10 years and am happily settled; Italy where my family originated and where I was myself married, started a family and subsequently separated; and the UK where I was born and grew up, on the North Sea coast of Kent.

(2) In conversation I often remark on the convenience of my German home, given its location roughly half way between my parents in the south of England and my daughter in Italy. Nevertheless, my regular to-ing and fro-ing on family visits is a symptomatic part of a divided sense of “home” and belonging, pulled in conflicting directions between Germany where I have lived and worked for the past 10 years and am happily settled; Italy where my family originated and where I was myself married, started a family and subsequently separated; and the UK where I was born and grew up, on the North Sea coast of Kent.

(3) 2011, in fact, will mark a sort of threshold in this respect, as from here on I will have lived more of my life abroad than in the country in which I was born. I have different attachments to each country, as well as a range of things which create a feeling of distance or ambivalence. Perhaps it is these feelings about the places we inhabit which we attempt to work out when they feature in our photographs.

(3) 2011, in fact, will mark a sort of threshold in this respect, as from here on I will have lived more of my life abroad than in the country in which I was born. I have different attachments to each country, as well as a range of things which create a feeling of distance or ambivalence. Perhaps it is these feelings about the places we inhabit which we attempt to work out when they feature in our photographs.

(4) My most recent trip to Genoa took place in January 2011, and it is the return journey of this trip which will provide the photographic terrain and narrative framework for this account. It centres around three key stages of the journey, the railway stations of Genova, Milan and Duisburg respectively. I can’t say for sure what has often interested me about train stations as photographic subjects. Perhaps they are early examples of the “in-between-places” which have proliferated in the modern world, places of transitions, of beginnings and endings where the order of our lives and relationships is subject to change. No doubt there is also a historical affinity between railway travel and photography, two of the main drivers in the dramatic alteration in the human perception of time and space which took place in the course of the 19th century; dislocated perceptions which underlie our experience of (5)

(4) My most recent trip to Genoa took place in January 2011, and it is the return journey of this trip which will provide the photographic terrain and narrative framework for this account. It centres around three key stages of the journey, the railway stations of Genova, Milan and Duisburg respectively. I can’t say for sure what has often interested me about train stations as photographic subjects. Perhaps they are early examples of the “in-between-places” which have proliferated in the modern world, places of transitions, of beginnings and endings where the order of our lives and relationships is subject to change. No doubt there is also a historical affinity between railway travel and photography, two of the main drivers in the dramatic alteration in the human perception of time and space which took place in the course of the 19th century; dislocated perceptions which underlie our experience of (5)  change throughout modernity and post-modernity; perceptions which, to come full circle, photography itself has often explored.

change throughout modernity and post-modernity; perceptions which, to come full circle, photography itself has often explored.

My journey starts, photographically, with a souvenir of a dark room, namely, the view from my hotel room window in Genova. The Hotel Cairoli is situated in the historical centre of Genova, embedded in the tangle of narrow streets and alleys which rise up from the ancient port. Space is generally tight in Genova, as steep hillsides begin their rise towards the mountains within a couple of hundred meters of the waterfront. Walking around the city, as a result, involves as much vertical displacement as horizontal, as the visitor negotiates as many staircases, public elevators or funicular railways as regular streets. Three or four centuries later and Genova might have developed along the lines of a mediterranean Manhattan, or Hong Kong perhaps, with its mountainous hinterland.

(6) The Hotel Cairoli is a curious blend: small and family run on the one hand, a “theme” hotel on the other. It is conceived as a sort of temple to 20-century avant-garde art, with each room decorated to approximate the visual style of a certain artist. I recall seeing Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevitch among others along my corridor, whilst my own room, number 13, featured the sculptor Alexander Calder. On the large wall facing the window in fact was a mural representing several sputnik-like satellites floating in space, presumably a 2-D version of the mobiles Calder is famous for.

(6) The Hotel Cairoli is a curious blend: small and family run on the one hand, a “theme” hotel on the other. It is conceived as a sort of temple to 20-century avant-garde art, with each room decorated to approximate the visual style of a certain artist. I recall seeing Piet Mondrian and Kasimir Malevitch among others along my corridor, whilst my own room, number 13, featured the sculptor Alexander Calder. On the large wall facing the window in fact was a mural representing several sputnik-like satellites floating in space, presumably a 2-D version of the mobiles Calder is famous for.

January 9th, the day of my journey, was grey and damp, but neither as cold or windy as previous days had been. I had given myself the whole day to make my way to Milan, enough time for the light of inspiration to shine for this assignment. Hopefully my camera and I would have more luck than suggested by the hotel room I had just left, camera 13, in Italian.

From the hotel I made my way first across Piazza Annuziata and along Via Balbi towards Principe Station. Shops were closed and (7) shuttered for the day and there were relatively few other passers by, mainly the present day combination of tourists and North African immigrants typical of the historical centre. Via Balbi also houses the main city centre building of the university, in particular the grand old founding faculties of Law and Letters, and it was more the absence of the student hubbub, rather than any particular presence, that was noticeable on this Sunday morning.

shuttered for the day and there were relatively few other passers by, mainly the present day combination of tourists and North African immigrants typical of the historical centre. Via Balbi also houses the main city centre building of the university, in particular the grand old founding faculties of Law and Letters, and it was more the absence of the student hubbub, rather than any particular presence, that was noticeable on this Sunday morning.

Recently Genova along with the rest of Italy has seen a round of student protests against university reform proposals from Berlusconi’s government. As a result, the graffiti marked walls of Via Balbi were more in evidence than ever, although what actually caught my eye among this contested wall-space was one isolated example which someone had actually taken the trouble to paint over. I initially assumed it had something to do with Via Balbi being a Unesco heritage site, and that someone had tried to restore one of the renaissance palazzi to a presentable condition.

(8) But then why only this one example among dozens of others and for that matter leaving the building as defaced as before, just differently so?

(8) But then why only this one example among dozens of others and for that matter leaving the building as defaced as before, just differently so?

This was not the first time I had found myself puzzling over Genovese graffiti and what it all might mean. In fact, a couple of days before my journey home I had found myself with the evening free and, disregarding my daughter’s concern for my personal safety, decided to brave the mean streets and alleyways around the old port in search of photographic (9)  discoveries. Here, as well as some stencil graffiti which was new to me, I met a familiar face from several years of inner city wanderings in Genova. I’d first encountered this face while exploring the old town on my first visit in 2005. The stencilled image is one of the most frequently seen in these narrow streets. Vaguely Che-like, the young woman gazes out from what seem to be strategically chosen corners where two alleys intersect. Having said that she’s rarely to be seen on the “main street” wall itself, but generally makes her silent protest from the shadows of what would be described as the side street in each case (although none of the streets in this port quarter are much more than a couple of metres wide). A generic resemblance to Che’s most famous of images is clear, although she doesn’t stare up and outwards towards a future free from oppression or exploitation. Instead, a street-fighting Mona Lisa, her inscrutable gaze directly confronts the passer-by (10).

discoveries. Here, as well as some stencil graffiti which was new to me, I met a familiar face from several years of inner city wanderings in Genova. I’d first encountered this face while exploring the old town on my first visit in 2005. The stencilled image is one of the most frequently seen in these narrow streets. Vaguely Che-like, the young woman gazes out from what seem to be strategically chosen corners where two alleys intersect. Having said that she’s rarely to be seen on the “main street” wall itself, but generally makes her silent protest from the shadows of what would be described as the side street in each case (although none of the streets in this port quarter are much more than a couple of metres wide). A generic resemblance to Che’s most famous of images is clear, although she doesn’t stare up and outwards towards a future free from oppression or exploitation. Instead, a street-fighting Mona Lisa, her inscrutable gaze directly confronts the passer-by (10).  Although intrigued I had never made the effort to enquire after her identity. Quite a lot of Genovese graffiti commemorates the G8 protests of 2001 and the protestors who were killed or injured by police, and I had always half assumed that ‘Mona’ was among their number. But after this trip, and with the 10th anniversary of that event just months away now, I finally did my overdue research. Of the two deaths of protesters at the event, one was indeed a woman, Susanne Bendotti. But it turns out that she died in a “traffic accident” (official version) at a police check on the French / Italian border on her way to the protest. The death of Carlo Giuliani, on the other hand, who was shot by the police during the protests, is frequently commemorated in graffiti around the city.

Although intrigued I had never made the effort to enquire after her identity. Quite a lot of Genovese graffiti commemorates the G8 protests of 2001 and the protestors who were killed or injured by police, and I had always half assumed that ‘Mona’ was among their number. But after this trip, and with the 10th anniversary of that event just months away now, I finally did my overdue research. Of the two deaths of protesters at the event, one was indeed a woman, Susanne Bendotti. But it turns out that she died in a “traffic accident” (official version) at a police check on the French / Italian border on her way to the protest. The death of Carlo Giuliani, on the other hand, who was shot by the police during the protests, is frequently commemorated in graffiti around the city.

These contested spaces, the graffiti, the violent protests, the brutality of the authorities’ response, all are symptomatic of a political struggle between the Italian left and right which dates back to the end of the second world war, and the defeat of the remnants of the fascist regime by the communist-led partisans. Later, during the cold war, Italy was on the frontline of the ideological battle between East and West, like Germany but without the wall to keep the two sides apart. This struggle has continued now for well over half a century, bubbling below the surface and occasionally erupting in its latest violent mutation, of which the G8 protests in Genova were the most dramatic recent example.

In the 10 years since then a familiar picture has emerged of far right extremists orchestrated by the police and intelligence services in rioting, violent disorder, and the fabrication and planting of evidence, all of which is then used to justify the subsequent repression of peaceful protesters. This, on a smaller scale, parallels the “strategy of tension” employed by far-right elements within the Italian establishment in the 70s and 80s, who used acts of terrorism to destabilise democracy by provoking reaction against left leaning governments of the time, with a long term view to re-instating a far-right dictatorship, along the lines of that established in the same period in Greece. The CIA, concerned to stop the communists winning elections outright, as looked likely, supported the strategy.

In 2010, thanks to the persistence of Italy’s independent judiciary, a certain justice was done, when no fewer than 25 G8 police officers and officials, previously cleared by government enquiries and acquitted in court, were finally convicted and received prison sentences on charges ranging from grievous bodily harm to the fabrication of evidence and perverting the course of justice. The policeman who fired the shot which killed Carlo Giuliani, however, remained unpunished, acquitted in an earlier trial. According to the court’s verdict the warning shot he fired into the air was deflected into Giulini’s head from a flying stone thrown by a demostrator. This despite the forensics report finding no evidence of the bullet having been deflected.

This gap between the official version and the truth that is clear to everyone has no doubt always existed, but surely it became starker for us all in the first decade of this century, marked as it was by the war in Iraq and the so called war on terror. In Italy however it has been a basic reality throughout the entire postwar period, with government collusion in corruption, organised crime and terrorism common knowledge. The early 90’s and the end of the cold war saw the total collapse of the traditional left and right parties in Italy, but the rise of Berlusconi seems to confirm the adage that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Thoughts of this kind were in my mind as I made my way up the graffiti scarred Via Balbi towards Principe train station. Piazza Principe outside the station serves the overlapping functions of bus terminal, car park and taxi rank. In the midst of the ill-defined borders between these three stands a monument to Cristoforo Colombo, Genova’s most famous son and, with his “discovery” of America, great grandfather of the globalisation which had brought the protesters to the city half a millennium later. He gazes out, presumably westwards, across the rooftops to the shoreline, where the ebb and flow of the waves could be an image of time itself, recalling photography’s folding of an irretrievable past into the present moment.

(11) The station itself is carved out of the foot of the steep hillside in a way typical for the region, except that in many towns up and down the riviera (Monte Carlo, San Remo) the lines and platforms remain embedded deep in the hillside; whereas here the whole seems to have been excavated, exposing the platforms to the light of day between the huge tunnels into which they disappear at each end. Perched atop these are the 19th and 20th century hotels and apartment buildings which provide the backdrop to the station. For a while I wander between platforms and station buildings looking for the images which might tell part of my story. Lacking inspiration, I head for platform 17 where the Intercity to Milano Centrale

(11) The station itself is carved out of the foot of the steep hillside in a way typical for the region, except that in many towns up and down the riviera (Monte Carlo, San Remo) the lines and platforms remain embedded deep in the hillside; whereas here the whole seems to have been excavated, exposing the platforms to the light of day between the huge tunnels into which they disappear at each end. Perched atop these are the 19th and 20th century hotels and apartment buildings which provide the backdrop to the station. For a while I wander between platforms and station buildings looking for the images which might tell part of my story. Lacking inspiration, I head for platform 17 where the Intercity to Milano Centrale  (12) is already waiting. There is the usual confusion among passengers as to which train this is, as the platform departure boards don’t seem to be working and the train is here well in advance of its expected arrival.

(12) is already waiting. There is the usual confusion among passengers as to which train this is, as the platform departure boards don’t seem to be working and the train is here well in advance of its expected arrival.

Intercity carriages on this line retain the traditional compartmental layout, and when I locate my reserved seat, I find I am the last to take up my place in this compartment. A slight re-arrangement of scarves, coats, magazines and limbs ensures that I can take my corridor seat without too much ado. Everyone is either reading or asleep. Directly opposite sits a sportily dressed woman in her thirties. In the middle seat of three, a man in his twenties sports a fashionable beard and reads what looks like a Penguin Classic, but I can’t make out the title. Finally next to the window a young woman already sleeping. On my side another young man and an older woman, who it later turns out is mother or some relative of the young woman asleep opposite her. They are the first in the compartment to speak to each other, in fact, when the younger woman awakens from her dreams an hour later.

(13) The first part of the journey takes place in and out of the darkness of tunnels, as the train heads directly into the hills, and it is with a similar rhythm that I feel myself drifting in and out of sleep. After a while the mountains open out into the Pianura Padana, the wide plain formed by the River Po as it winds its way across northern Italy to the Adriatic. The flat landscape is punctuated by groups of trees and farm buildings, and these gradually turn to warehouses and trading estates the nearer we get to the city.

(13) The first part of the journey takes place in and out of the darkness of tunnels, as the train heads directly into the hills, and it is with a similar rhythm that I feel myself drifting in and out of sleep. After a while the mountains open out into the Pianura Padana, the wide plain formed by the River Po as it winds its way across northern Italy to the Adriatic. The flat landscape is punctuated by groups of trees and farm buildings, and these gradually turn to warehouses and trading estates the nearer we get to the city.

One type of dream that I often half-remember are those recurring ones which feature some kind of journey, most often by train, and as I wake up to find myself still amongst my travelling companions in the Milan-bound compartment, I struggle to retain an image of the world from which I have awoken. In W.G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz, the main character makes a connection between this moment, familiar to us all, and the processes of pre-digital photography. In my photographic work, I was always especially entranced, said Austerlitz, by the moment when the shadows of reality, so to speak, emerge out of nothing on the exposed paper, as memories do in the middle of the night, darkening again if you try to cling to them, like a photographic print left in the developing bath too long.

I use the last part of the journey to finish the book I have been reading, Manituana, by Wu Ming, an Italian writers collective. The novel fictionalises the story of the North American indian nations loyal to and “protected by” King George around the time of the war of independence, and how the victory of the land hungry colonists, roughly mid-way between Columbus and the present day, effectively seals their fate.

Shortly after 3pm the train draws slowly into Milan Central station, passing by the derelict signalling tower cabina A, a  (14) forlorn relic embracing six incoming lines or more. Milan’s thick grey winter covering of cloud and pollution is present as ever. As this is the last day of the Christmas and New Year holiday there are a lot of people on the move and the station is busy. Loosely modelled on the Union Station in Washington DC, Milano Centrale took 20 years to complete, and was opened in 1931 by Mussolini’s son-in-law and Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano. The building combines the liberty and art deco influences of its original early 20th century design with the fascist bombast designed to express the greatness of the regime. As I wander its vast spaces, reaching up to 70 meters in height and criss-crossed by travellers in (15)

(14) forlorn relic embracing six incoming lines or more. Milan’s thick grey winter covering of cloud and pollution is present as ever. As this is the last day of the Christmas and New Year holiday there are a lot of people on the move and the station is busy. Loosely modelled on the Union Station in Washington DC, Milano Centrale took 20 years to complete, and was opened in 1931 by Mussolini’s son-in-law and Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano. The building combines the liberty and art deco influences of its original early 20th century design with the fascist bombast designed to express the greatness of the regime. As I wander its vast spaces, reaching up to 70 meters in height and criss-crossed by travellers in (15) couples or family groupings, I feel a sort of estrangement, a combination of the safety of anonymity and the virtual invisibility that comes from being alone in a busy foreign city. Milan is Italy’s fashion capital of course, and a recent refurbishment has transformed the station into its cathedral. New escalators set on a very slight incline glide the travellers slowly past the windows of designer boutiques lined up for display on either side. The shop windows compete with

couples or family groupings, I feel a sort of estrangement, a combination of the safety of anonymity and the virtual invisibility that comes from being alone in a busy foreign city. Milan is Italy’s fashion capital of course, and a recent refurbishment has transformed the station into its cathedral. New escalators set on a very slight incline glide the travellers slowly past the windows of designer boutiques lined up for display on either side. The shop windows compete with  (16) gigantic posters and video screens for the attention of passers-by. Images and their reflections multiply as in a vast hall of mirrors. As my departure time approaches I gradually make my way back through the vaulted halls towards the platform where the overnight train awaits that will take me, via Basel, Mannheim and Koblenz, to Duisburg in the industrial north of Germany.

(16) gigantic posters and video screens for the attention of passers-by. Images and their reflections multiply as in a vast hall of mirrors. As my departure time approaches I gradually make my way back through the vaulted halls towards the platform where the overnight train awaits that will take me, via Basel, Mannheim and Koblenz, to Duisburg in the industrial north of Germany.

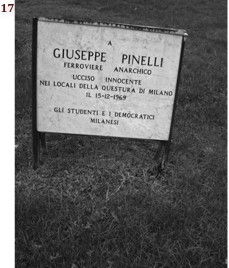

Not far from Milan’s real cathedral, in Piazza Fontana, the Italian far right initiated its strategy of tension on December 12, 1969, with the bombing of the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura. The explosion, in which shadowy elements in the Italian establishment and secret services recruited local neo-fascists to build and plant a bomb, was initially blamed, as intended, on far-left student and workers groups which were strong at the time. 17 people were killed. An anarchist railway worker, Giuseppe Pinelli, was arrested, questioned and charged with the bombing, in an attempt to pin the bombing on the leftist groups. Knowing the charges wouldn’t stick, the authorities decided to do away with the main suspect, and faked Pinelli’s suicide. Perhaps not surprisingly, the post-mortem revealed his injuries to go far beyond what would have been caused by his alleged jump from the fourth floor window of the police station. Months later the police officer suspected of his killing was cleared in court, but subsequently murdered in revenge by the Red Brigades. Meanwhile the false trail laid down with the arrest of Pinelli gave the true perpetrators of the bombing time to cover their tracks, and to this day no-one has been found guilty of the attack.

(17) By the time I arrive in Duisburg station dawn is approaching. As I wait for the local train which will take me the few miles to my final destination, I explore the station in search of one or two images to accompany the end of my story. Duisburg station somehow missed out on the drive to refurbish Germany’s main train stations which came with the hosting of the world cup in 2006. The 19th century iron and glass canopy which covers the central part of the platforms is nowadays far from weatherproof. Smashed or missing glass panes compete with the rusty green framework in their desperate appeals for maintenance. What strikes me most is how the northern and southern walls, although identical in construction, look strikingly different in the half light before dawn. Seen through the glass panels of the northern wall, neon lights in the street outside combine and recombine in unexpected ways.

(17) By the time I arrive in Duisburg station dawn is approaching. As I wait for the local train which will take me the few miles to my final destination, I explore the station in search of one or two images to accompany the end of my story. Duisburg station somehow missed out on the drive to refurbish Germany’s main train stations which came with the hosting of the world cup in 2006. The 19th century iron and glass canopy which covers the central part of the platforms is nowadays far from weatherproof. Smashed or missing glass panes compete with the rusty green framework in their desperate appeals for maintenance. What strikes me most is how the northern and southern walls, although identical in construction, look strikingly different in the half light before dawn. Seen through the glass panels of the northern wall, neon lights in the street outside combine and recombine in unexpected ways.

The southern wall, by contrast, has no busy street streets or brightly lit areas directly in front. The entire glass length seems to be shrouded in darkness. Only once, as I walk the otherwise deserted platform alongside, is the shadow of a tree cast faintly on the frosted glass, recalling the ghostly projections on the wall of a camera obscura as its branches shift in the wind.

Nessun commento